|

by Juanita Canzoneri

Welcome to an ongoing blog about how to sell your artwork through Commonwheel Artists Co-op. This timely tip is brought to you by our annual Holiday Market. Option 1—Holiday Market! Submit work to for our Holiday Market jury. This year it will take place on September 12 and we are accepting samples of your actual work, along with the Jury Form and Jury Fee of $10 on September 10, 11, and 12 from 10 am to 6 pm daily. Jury Forms and information are available at commonwheel.com/holiday-market.html .

0 Comments

Virginia Peach Blossom Virginia Peach Blossom by Juanita Canzoneri Jo Gaston grew up on a farm in southwest Missouri. Grandparents on both her mother's and father's side lived on farms nearby. Some of her earliest memories are of vegetable and flower gardens and of the livestock. Jo creates watercolors of the ranch and garden subjects she has known since childhood. The realistic details of her paintings make her subjects easily recognizable as she uses light and color freely to intensify her impressions of the inherent abstract forms. Attractive forms, textures, and colors are present and waiting to be recognized in many of her subjects especially in vegetables, flowers and Western tack. Although, she admits she finds that turning them into art is hard work. She has to choose thoughtfully, stand close, observe carefully, and work within the fundamentals of artistic composition. The intricate shapes and glowing colors of vegetables and flowers appeal to her. She uses saturated, vibrant pigments to dramatize their form and texture. She finds an endless variety of form, texture, and light and color in vegetables and flowers. From warm, rich browns to bright, whimsical pinks, purples, and blues, her palette grows with each painting. Form, texture, light, and color are there waiting in most of her subjects, but composition and value are the most important elements in her work. She combines and positions her subjects to achieve the strongest visual effect. Her goal is always a composition that intrigues and rewards the viewer, and dramatizes the features that originally interested her to the subject. For the pieces in “Botanical Expressions” Jo begins a painting by selecting a subject with strong, interesting design elements. Prominent colors and light levels also direct her choices. The hibiscus blossom that is a subject of Kathleen’s jewelry and her watercolor painting attracted her with exactly those desirable design elements: colors, and light levels. Having chosen a subject, she does several drawings until she has an outline that reads well, one with a clear center of interest and a combination of shapes and lines that will guide a viewer into, and out of, the eventual painting. Then she adds shading to help with decisions about the direction and intensity of light and shadow. These decisions about values are critical because with transparent watercolor one cannot go back to lighten something that’s too dark. When she’s sure of basic shapes and light levels, she does a color study by blocking in principal colors. Those blocks of color tell her for the first time whether the light, color, and shape will come together well. Going from the color study to the final painting takes hours of attention to shading, texture, and detail—using multiple layers of transparent watercolor to get the right balance of darkness and light, adding intricate details to emphasize texture and bring out important features. That sounds like a lot of work for a single hibiscus blossom, doesn’t it? Kathleen and I agree that what we create does take plenty of effort and time, but somehow work doesn’t seem the right term for what we do. We take delight in the creating of our jewelry and paintings, and we very much hope you’ll enjoy seeing the results. Gallery Show featuring Sculpture and Paintings by David Caricato Opening Reception March 18, 5-8 pm Show runs through April 11. Regular store hours are 10 am-6 pm daily. Article and photographs by Juanita Canzoneri David Caricato has been making art for over 40 of his nearly 70 years. Most of that time he worked with sculptural forms in wood and other natural materials. His early work uses long gourds as a base for the pieces he calls “Earth Dancers” which include design elements from southwest First Nations tribes. He began incorporating raven masks worked in the northwest First Nations style as a humorous juxtaposition of ideas.

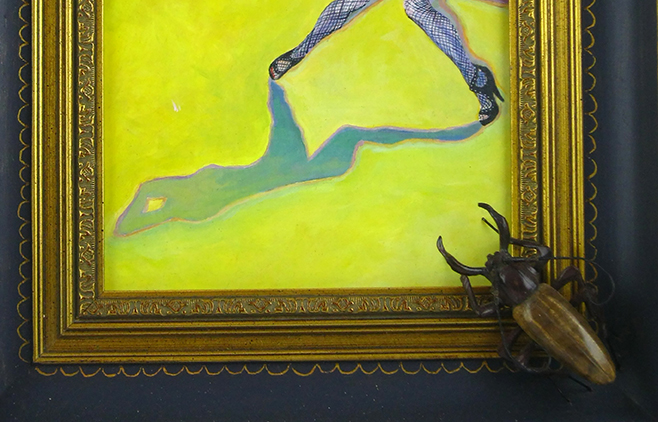

The raven masks, as well as other mask styles, have by now found their way into many other sculptures that don’t incorporate the “Earth Dancer” shapes. With the most recent change in the economy he diversified to making small figural paintings in acrylics. He can sell the paintings at a lower price point since they come together quicker than his larger sculptures do. But ever the dyed-in-the-wool wood worker he hand-carves many of the frames for his paintings. For his paintings he works with a limited number of models, over several years. Pointing to one painting he told me, “I’ve worked with her over 3 boyfriends and breakups. I think the guy she’s with now will be a keeper.” The pieces that come from these modelling sessions are collaborative. He might have an idea for where he wants to start, or the model may want to try something. The sessions are photographed and then both he and the model look at the photos and make changes. With his paintings, which are typically no more than 6”-8” tall, his studio is the kitchen island or in his living room. He had a studio in an outbuilding on his property that’s more conducive to his sculptural work, with a tool bench and dust catchment system he works year round. Pulling out a piece he’s working on he explained some of the woods he worked with created dust that was quite dangerous to inhale. David’s goal with his art is to push buttons and find where the boundaries are. He is making the type of art that he wants and is a self-diagnosed wood hoarder. His figural art deals with the human form, including many nudes. Getting the musculature correct is highly important to him, even with his smallest canvases. This gives his paintings and sculptures a realistic quality. But the humor in his art lends a charm and warmth to that realism. And there are times when David expresses his political views in a very tongue-in-cheek way with his work. David is a Pueblo native with two undergraduate degrees, one in Graphic Design and one in Industrial Arts/Woodworking. He has been showing galleries throughout the Southwest, Washington state, Florida, and New York. He recently had a one-man show of the same name at the Sangre de Christo Art Center and has received numerous awards, including Best in Show and First Place in Sculpture at the Colorado State Fair Art Show. by Juanita Canzoneri So much work has been completed by so many people in what seems like only a few days. The painting is complete, the wall panels are completed and installed, the trim is up and the new carpet is installed. The windows in the front of the store have been treated with a UV and heat-resistant film to help preserve the artwork displayed by them. On Feb. 29 we moved all the furniture out of the store, much of it into a rented U-Haul truck. The carpet installers came in the next day. They even rolled the carpet out in the street to allow them to make some of the longer cuts. At one point we had to stop traffic so no one drove over it. On March 2 most of the detail work was completed. On the 3rd all the fixtures were cleaned and reassembled and set in their new locations. Members brought their work back in to restock the store on March 4 and 5 and we opened for business again on March 6. There’s still a little more work to do. We need to complete the new gallery space and clean the storage spaces that were used to house items during the renovation. But the only deadline ahead is the hanging of the next gallery show, which will happen on March 16. And the gallery is now in its own private space so that work can continue without much interruption to regular business. I can say, though, that our Marketing Manager (that’s me) will be glad to get her office space back again. That space is part of the gallery space work yet to be done. By Juanita Canzoneri

Before we start there’s something you should know about me. I’m not a potter. I can’t stand the feel of raw clay. But put that same lump of damp, sticky stuff in the hands of someone who really knows what they’re doing and I am mesmerized. It’s just dirt but they can make something so beautiful it’s humbling. So while I truly hate the feel of raw clay (I’ve tried to like it but I’m hardwired for glass), I love potters. As part of an artist’s co-op I get to talk about their technique and sell their work. Even better, I get to hang out with them and learn to love their endearing, and often clay covered, quirks. Take Deborah Hager. She has this thing for shino glaze. And while she hates crawling in her own work, she holds another artist’s heavily crawled shino piece as one of her prized possessions. (“Crawling” is when the glaze forms an irregular texture of bare spots of clay or beads of glaze on the surface of the piece. To me it can look a little like cellulite.) In her shino work Deborah loves the depth of color and layering effects, and that it doesn’t run in the kiln. She’s also enamored by the history of shino glazes. Shinos originated in the 16th century as Japan’s first white glaze. It was made from local feldspar which, when fired, produced a white glaze with soft sheen and subtle depth. Original shinos were fired in wood fire kilns using pine as fuel. These firings took several days to reach the desired temperature of approximately 1200° Celsius (about 2200° F or Cone 6). Although there are several theories, the origin of the name “shino” is not known. Shino glazes were used in the ancient kiln sites of Mino and Seto in central Japan, centers for ceramic exploration and production. One reason for the specific location for these kilns is because of the local clays and minerals available. This distinction becomes important with the development of “American Shino” glazes. Shino was one of the greatest achievements in this region during the Momoyama era (1573- 1600) when Japanese the culture moved from mediaeval to early modern. It was a time of artistic, cultural, and political advancement. This era also saw the emergence of the tea ceremony, which integrated the art of ceramics as a significant part of the process, reflecting the artistic values of the Tea Masters. Many of these Tea Masters valued and used tea bowls glazed with shino. Shino dropped out of fashion and apparently disappeared from use from the 17th century until the 1920s when Arakawa Toyozo (1894-1985) and Hajime Kato (1900-1968) revitalized the glaze in Japan through the study of shino pottery shards from the Momoyama period. In America, Warren Mackenzie is attributed with the most recent Shino revival and exploration. In 1974 he challenged his graduate students to recreate a traditional shino glaze using minerals that were available in America. This was the advent of American shinos that facilitated an onslaught experimentation with the glaze and renewed artistic interest. One of Warren’s students, Virginia Wirt, created a recipe which included soda ash and spodumene. Her new recipe included carbon trapping, which added depth to the new shinos. This is the effect of smoke or other organic materials from the clay body or kiln fuel being “trapped” in the glaze as it’s melting. The results can be mottling, shadowing, or lines that form in the glaze. The effect can be somewhat elusive. Malcom Davis also picked up and advanceed shino glazes by adding redart clay and larger amounts of soda ash. (In mixing a new batch of shino glaze one day he discovered he was out of spodumene. Rather than put off firing until he could get more he doubled up on the soda ash and liked the result.) According to Davis “shino is the glaze that breaks all of the rules, no other glaze varies so much depending on how it is applied, dried, and fired. Shino’s are elusive and ephemeral, it is all about the Alchemy.” In the 1970’s and today, minerals that end up being used in glazes are generally mined for larger industrial uses. This provides for a more uniform particle size than would have been created with the earlier feldspar mined for Japanese shino. In addition, different mines produce a slight variation in the mineral content of the final product. This variance can change the resulting glaze in both large and small ways. A desired effect may become more unstable, or disappear entirely. While the most prized early Japanese shinos produced a thick white glaze (described by one writer as being coated with fat) that often had a translucent quality or a soft sheen, shinos then and now turn out a variety of colors—white, orange, russet, brown, and black. The color that results depends on several factors. The thickness of the glaze, how soon it was fired after it was applied, how it was dried, where it sat in the kiln, the type of kiln, the type of clay body, and on and on and on. One list I read started with 16 variables which included the type of water used to mix the glaze. Shino is prized with being a very stable glaze, in that it doesn’t run when it’s being fired. That translates for us non-potters to less stuff melting onto and messing up kiln shelves. But then there are other effects, like “carbon trapping” and “crawling”, which are less consistent and often highly sought after for that reason. Listening to some potters talk about these effects is similar to listening to an addict. There’s that thing they got once that they’ve spent the rest of their career trying to recreate. With other glazes and techniques the kiln is useful for firing and finishing the pottery. With shino glazes, the kiln becomes a design tool. Glaze color and texture is affected by where the piece sits in the kiln, how much oxygen or smoke is present or absent, the type of kiln (gas, electric, wood), the firing temperatures, and so on. Each variable can change the outcome of the piece. Potters describe whole kiln loads that have come out a flat ugly orange, or disintegrated soon after the kiln was opened. The artists featured in “Shino Smackdown” have experimented with this evocative glaze and are standing on the shoulders of these giants from the past; some of whom we know and some who are lost in the mists of history. Each artist participating in the show was asked to provide their personal shino recipe and at least 6 mugs alongside other work. Each artist in this show stretches and recreates the shino recipes of their predecessors. The possibilities of new glazes and new effects are endless. And so the quest continues to capture the glaze that refuses to obey. It is that very nature that fuels the momentum of continuous exploration and creation.  by Juanita Canzoneri Commonwheel Member since 2004 and Marketing Manager The back part of the Commonwheel Artists Co-op building sits directly over Fountain Creek. From my office area in the Creekside Gallery I get the opportunity to engage with customers about our noisy neighbor. Manitou Springs is within the Fountain Creek Watershed. This watershed encompasses approximately 928 square miles with a perimeter of 160 miles. The headwaters of Fountain Creek begin near Woodland Park on the eastern face of Pikes Peak and join with Monument Creek near downtown Colorado Springs. Monument Creek (and Fountain Creek along with it) ultimately ends up in the Arkansas River near Pueblo, Colorado. The creek is fed by snow melt, runoff from natural springs, and rain water. Ruxton Creek (which runs along Ruxton Ave.) feeds into Fountain Creek at Soda Springs Park in Manitou Springs. In 2013, one year after the Waldo Canyon Fire, Fountain Creek overflowed its banks on 2 occasions and flooded, among other places, the basement of Commonwheel Artists Co-op. In August 2013 water and debris entered our basement through an adjoining property. The water level came to within 6 inches of the basement ceiling. The flood occurred on a Friday afternoon/evening. Several of us headed over to the shop on Saturday morning to see what we could do. We could see the high water mark in the stairwell to the basement and a neighbor had sent us photographs she’d taken through the broken basement window. Inside was a jumble of debris, mud, and what had been the contents of our basement. The removal work started within a couple days and lasted for weeks. That Saturday is still a bit of a blur to me, except for 2 points. As I was walking to the store in my steel-toed boots I passed a family of 4 with bright white tennis shoes on. They were visiting from out of town and hadn’t heard about the flood. We were about a block from the mud zone at that point. Then as I was getting in my car to go back home I noticed a guy on a Vespa driving past me. He had a shovel with him standing straight upright. He obviously came into Manitou to volunteer in the clean-up efforts like so many other people. The sheer numbers of people who came out to help clean was staggering. So much so that the Manitou Art Center (then the BAC) stepped forward to act as a clearinghouse for volunteers and supplies. Again in September 2013 another flood left several inches of water in the basement but the high creek waters damaged some of the support struts under the back part of the building, forcing full and partial shop closure for the better part of 2 months. Tens of millions of dollars in flood mitigation has been undertaken since 2013 by various organizations—CDOT, Manitou Springs, forest districts, and CUSP. To date these efforts have proven effective in keeping the worst of the debris out of Fountain Creek, or at least out of Manitou Springs. Photos of the aftermath and cleanup from the August 2013 floodPhotos of Fountain Creek during the September 2013 flood |

Juanita Canzoneri

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed